This past spring semester, I taught a 200-level history class titled “Disaster & Disease: Society and Environment in Latin America, 1450-2017.” The goal for the course was to let students investigate how climate, disease, and environmental changes impacted societies. How did humans face these challenges and adapt to them? And what does this tell us about those societies? One of the connecting questions for this course was how societies at different points in time interpreted and interacted with their environment. Based on several case studies, we moved chronologically from fifteenth-century pre-contact societies through the colonial period (1490s-1820s), covered the nineteenth and twentieth century national period, and ended with recent examples like the 2010 earthquake in Haiti or the devastation of Caribbean islands like Puerto Rico after the hurricanes in 2017.

For one section of the class, I asked students: “Earthquakes, viruses, and hurricanes. They make news, but do they make history?” The question encouraged students to challenge a tradition of seeing humans as isolated actors at the center of historical narratives. For this section of the course, we looked at various natural disasters at different points in time. After discussing the 1746 earthquake-tsunami in Lima (Peru) on Tuesday, in the following class students split up into small groups and read short articles on earthquakes in twentieth-century Latin America (Argentina 1944, Nicaragua 1972, Guatemala 1976, Mexico City 1985).

For our class discussion, I prepared a series of short news clips from each year, to give students an idea of the media coverage for each specific event and to break up the rhythm of the class discussion or lecturing. When we got to discussing the earthquake that shook Guatemala on February 4, 1976, I we watched a YouTube video with material from the Red Cross – Red Crescent Historic Film Collection. The clip showed impressions of destroyed houses and roads, while the narrator announced in a somber tone that the disaster had killed 20,000 people and destroyed the homes of 1.2 million Guatemalans.

So far, nothing unusual. Just your ordinary use of multimedia to enrich the learning experience – until….

I was just about to close the web-browser and lead my students to another discussion about what the aftermath of a natural disasters can reveal about a society’s underlying power hierarchies, socio-economic structures, the role of the church etc. etc. … when I caught a glimpse on the comment section below the video:

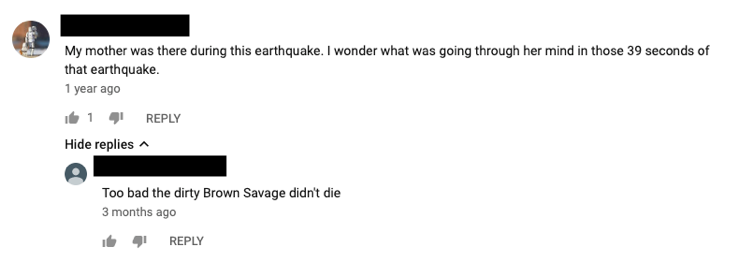

[Comment 1]: My mother was there during the earthquake. I wonder what was going through her mind in those 39 seconds.

[Comment 1]: My mother was there during the earthquake. I wonder what was going through her mind in those 39 seconds.

[Response to Comment 1]: Too bad the dirty Brown Savage didn’t die.

I had my students read the comments out loud and the room went from silent compassion for the first commentator’s family to angry murmuring about the response. I ask them to articulate their frustration with the second commentators statement and point out what rhetorical elements they could discern here (we had previously discussed the issues with the term “savage” in the context of the Ecologically Noble Savage Debate).

Out of this grew a passionate debate about present-day racism and how Latin America is portrayed in U.S. media today. Students immediately linked this example to other disparaging comments that appeared on social media in the wake of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, or the 2017 hurricane in Puerto Rico. I treated the Youtube clips as simply supportive material, but this unexpectedly led students to passionately connect historical events with present day issues and debates. What I imagined to be an illustrative addition became the main point and a lesson in how, as instructors, we can never fully map out how a class will go.

P.S.: As I am finishing this blog post, I am also grading the final essays students wrote for this class. Passionately, witty, and sharp-eyed, they connected major themes relating to environmental history, racism, environmental justice, (post-)colonialism, Latin American economic history, and environmental crime. Bien hecho, mis amigxs!