On the morning of Monday, March 9, I reached out to a supervisor suggesting that we begin thinking about offering a virtual version of NYU’s Intro to Programming tutoring lab. At the time, my concern was primarily for immunocomprised staff and students. CSCI-UA.0002 (Introduction to Computer Programming in Python) enrolls many hundreds of NYU students every year, supported in part by a team of roughly a dozen graduate and undergraduate student tutors manning a drop-in tutoring lab seven days a week. Especially during midterm season, traffic is high and the space is crowded.

Rather than wait for an “official” statement from the university, I figured we could begin developing a workflow that would best meet student needs while being conscious of tutor limitations and concerns.

By 6 p.m., we had received a university-wide email informing us that all on-campus classes and activities were to cease in roughly 24 hours.

In “Thoughts & Resources for Those About to Start Teaching Online Due to COVID-19,” HASTAC Co-Director Jacqueline Wernimont reminds us that many instructors who have transitioned to remote teaching in the past few weeks are doing so “for the first time and under duress.” Despite the proliferation of misguided articles to the contrary, now may not be the time to take on the labor of carefully-scaffolded, critically-robust online course or learning environment design. (Indeed, we’re not teaching “online courses” at all, but emergency response versions of courses often designed for synchronicity, in-person delivery, ‘regular’ access to resources, and the relative absence of the acute material and emotional strains of a literal pandemic.)

That said, there are ways to incorporate elements of critical digital pedagogy in our moment, and especially those elements that foreground compassion, transparency, and a commitment to the broader socio-epistemic questions of what and how we’re permitted to know.

On March 13, I hosted a HASTAC Digital Fridays webinar on humanities approaches to critical digital pedagogy. The webinar recording is available on YouTube, and the slide deck I used is viewable via Google Drive.

Rather than recap the webinar here, I want to offer an overview of four strategies you might explore in your now-digital learning environments.

I’ll be the first to acknowledge that they mostly place the onus on the instructor, and that the labor of thoughtfully supporting students often falls on instructors in contingent roles (like graduate students and adjuncts) and on instructors of color. None of them is “easy” to implement, but the work of critical pedagogy is never frictionless. And there are, of course, many more than the ones I’ve outlined here, and many amazing practitioners to look to for models. I’ve linked a few throughout and welcome suggested additions.

I’ve taken an auto-ethnographic approach because these methods have emerged largely from my work as a learning designer and educator, and because I think it’s a useful model.

1. Have the “meta” conversation

Every time my partner — a freelance motion designer — initializes a file transfer, my Internet connection is immobilized. Simple tasks, like loading fairly light web pages, become near-impossible, screeching my work(-from-home-)flow to a halt. My orange tabby seizes these moments of slowness as opportunities to splay out across my keyboard, swatting at my wrists as I attempt to maneuver around her and occasionally sending off gibberish emails. (If you’ve been a recipient of my cat’s emails, I apologize.)

These are, admittedly, minor gripes in a pandemic landscape. But they force me to confront my inability to work “seamlessly” amidst the spatial and technical limitations I’m facing, just as hours spent guiding my tech-illiterate parents through online unemployment applications and fielding housing insecurity concerns from students force a consciousness of my waning emotional bandwidth and their very real material crises.

It’s okay to bring your uncertainty and confusion to your online teaching. Acknowledge, and encourage your students to acknowledge, the practical and affective limitations you’re all facing, taking great care to reassure students that their physical and mental health should come first. Make space for students’ mourning. (By extension, try to avoid placing the burden of your own emotional despair on your students.) Rather than “pushing through it,” make the mess present. Ask your students what you can do, collectively, to meet their learning needs right now.

You might collaboratively consider:

What are the technical requirements of our current remote learning setup? Are they accessible (to you, or in general)?

What does remote instruction assume about students’ living conditions? What about learning styles? How would you describe the pedagogical approach we’re taking?

What has been difficult to use? What alternatives to this setup can you imagine?

What structural / systemic barriers might there be to deploying these alternatives (e.g., enterprise software licensing, departmental pressure, labor)? What might they tell us about systems of valuation more broadly?

Will you let me know if our remote learning situation isn’t working for you? Perhaps you’re in a different time zone, are having bandwidth issues, or simply need time away from being “online.”

2. Examine the rhetorical tradition of the platform, together

A couple years ago, I was lucky enough to serve as a project manager and user experience consultant on a software build for humanities research and pedagogy. Specifically, my team was prototyping a suite of browser-based tools for faculty and students to manage and visualize their data sets in long-term project-based learning environments. However, much of our decision-making went undocumented. Every library or plugin deployed is, ultimately, an ethical and pedagogical decision in addition to a technical one, but we rarely grappled with these questions in a way that made them readily legible to the end user.

All software emerges from a socioeconomic and discursive matrix, but most software suffers from a lack of critical self-reflexivity. Regardless of the technologies your remote learning setup comprises (e.g., Zoom, Google Classroom, WebEx, Canvas), close reading of the interface and media archaeology are powerful and scalable pedagogical strategies.

In my course on data and literature, I use Dr. Wernimont’s incredible scholarship on human quantification to help my students draw connections between contemporary finance practices (like Lehman Brothers’ Repo 105, and the lived consequences of the subsequent recession) and long, violent histories of ledgering (like records of Henry Lehman’s 19th-century slave “purchases”). The logic of tabulation and the “ordering” of humans is pervasive, and one of the many traditions you might ask your students to explore.

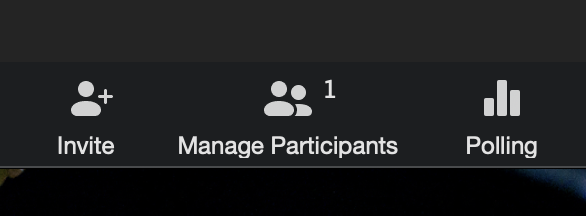

For example, the host’s control bar in a Zoom meeting includes a button labeled “Manage Participants.” (Why) might this be important? What does it tell us about the rhetorical register of the software’s interface, and the technological tradition(s) to which it belongs? Whose authority is “built in” to the interface, and (how) can it be challenged? Can we find echoes of this language in the texts or media on our syllabus?

You might also ask:

What are the data privacy and surveillance traditions at work in this piece of software? Whom do they privilege?

What might we find if we “close read” advertising, press releases, or stock charts related to this software company?

If you had to write epistemological or ethical documentation for this software, what might it look like? How would it engage intentionally with questions of race, gender, ethnicity, class, sexuality, and ability? What additional information would you need? How would it tie into the literary or historical content and methods we’re studying in this course?

3. Rethink content delivery, assignments, and grading

Over the past week, I’ve seen a number of academics share email templates provided by their departments or schools, many meant to be dispatched to students “falling behind” during remote instruction. The values encoded by communications like these are familiar: rigor, visibility, productivity, attendance, active participation (often synchronously), obligation, accountability. As you revisit your syllabus, reflect on the social registers of these and other values that undergird our evaluation protocols in higher education.

Try asking yourself:

What kind of asynchronous learning experiences are possible (given your very real constraints)? How might they actually be better suited to your teaching objectives than synchronous content delivery? How might you discuss the ways in which synchronicity and visibility/seeing are valued in higher education with your students? What other senses can you engage?

Consider decreasing the number and/or changing the modality of your course assignments. What kinds of creative or expressive work can your students do? How might you make room for them to process their uncertainty and anxiety? For example, art, poetry, and other kinds of “making” can be welcome outlets. For those interested, is there virtual community organizing work that is both viable and relevant to learning goals?

Many universities are already giving students the option to convert their course grades to pass/fail this semester. Whether or not your institution is among them, what adjustments might you make to your assessment procedures? Can you express to your students that your plans for assessment are still in flux, that they have you confused? (See also: Alexander Jones’ “Thoughts on Admitting Defeat.”)

As Jesse Stommel notes in “Ungrading: An FAQ,” grades are “baked into our practices and reinforced by all our (technological and administrative) systems.” What might it look like to resist these systems (in big or small ways)? Is it possible to prioritize techniques like student self-evaluation and reflection? How does your evaluation methodology account for differences in learning styles and multi-modal work? Especially given the difficulty of administering “traditional” examinations under social distancing circumstances, what forms of formative and/or summative assessment are possible? Are they accessible? Just?

4. Pay heed to the body

There are three windows in my Brooklyn apartment. The window in our main living and working space opens onto an airshaft: if I were to dismount the safety bars and extend my outstretched arm, I would be able to touch the adjacent wall before my elbow exited the building. In the bedrooms, one window is obscured by a rusty fire escape, and the other looks onto a courtyard flanked on all sides by edifices. Inside, it is always nighttime.

After several weeks of social distancing, the perennial darkness has begun to deeply disorient me: even while working “standard” hours from home, I lose track of hours and days, sleep poorly, and am enveloped by fatigue and derealization. The disturbance of routine — which, for me, was defined primarily by leaving for and returning from work — introduces new mental health challenges and exacerbates facets of my mood disorder. I am painfully aware of my sedentariness, and of the tension my body holds.

Software like Zoom would have us believe that we are, first and foremost, floating heads. But embodiment is central to our learning and teaching, now and always.

If you deliver content synchronously, what might it look like to set aside time for body mindfulness? Can you encourage students to periodically check in with their bodies (e.g., to check their posture or do a sensory awareness grounding exercise)? What resources has your university made available to support students in moving and noticing their bodies?

In what ways can your syllabus incorporate motion and/or other sensory experiences that don’t rely on screen time?

For whom might the disruption be particularly difficult? Keep in mind that students may be facing housing, income, and food insecurity; absence of a consistent, quiet space to work; unwanted return to volatile home environments; and other extremely difficult situations.

Physio-social isolation, anxiety, and precarity can make the management of developmental disorders, mental illness, and eating disorders exceptionally hard. Do your communications (course content, emails, forum posts) avoid language that might be alienating to students with these conditions?

If you have students who have been granted accommodations, what changes need to be made to ensure they are supported?

If I can support you or connect you to additional resources, please feel free to email me at gafsari [at] nyu [dot] edu.