Image description: a row of texts I’ve assigned in my literature courses related to human rights, transnational American literature, migration, and Chicanx studies.

This blog post provides a detailed account of how I implement the “Navigational Log” in my courses to scaffold the skills of close reading, critical thinking and reflection, listening, and dialogue. It builds on the snapshot provided in the “progressive pedagogy” post.

Introduction – does teaching literature sustain white supremacy?

I am a white, female educator who has worked in K-12 and higher education for thirteen years. With renewed urgency, I have been asking myself: am I truly doing the anti-racist work I need to be doing in my classroom? Does teaching close reading and literary analysis really help fight oppression? On paper, the courses I teach would be seen as doing so: “Human Rights and World Literature,” “Introduction to Chicanx Literature,” “Literature of the Americas,” and “Literature of Migration, Travel, and Exile” include plenty of assigned reading from marginalized voices. But the reality is that simply reading from and about these voices, while crucial, is not effective enough as anti-racist pedagogy. In fact, teaching antiracism through exposure alone risks making things worse. Why isn’t encountering the story of someone whose identity you do not share (i.e. “the other”) enough as a practice of antiracist pedagogy? Because it relies on students having a set of communicative and analytical skills that they have never been taught; indeed, they’ve been taught quite the opposite.

Students often walk into my class thinking that “analyzing” literature means dutifully recounting a text’s plot, reciting the supposed authoritative meaning of its symbols and metaphors and other such blunders of too many high school English classes pressured by standardized testing. Even more troubling is that they arrive in my classes thinking that “analysis” simply means scrutinizing a text for supposed “bias” against an imaginary neutrality. I’ve observed these trends among my white students, my students of color, my financially-privileged students at a wealthy R1 university, and my first-generation students at a local public college. While this training may seem like nothing more than a benign annoyance for a college literature professor, its effects are much more dire. When paired with straightforward “exposure” to oppressed and silenced voices, teaching literature in this manner does little more than further entrench long-circulated racist ideas. For an analog, we can look at the way that memorializing hashtags, intended to increase the visibility of black death, seem to become little more than emblems of our inurement to these spectacular acts of violence.

The “Navigational Log” is one instructional tool I’ve developed to help my students unlearn this training and learn to approach literary analysis in a more nuanced, personal, and rigorous way. Through this and other practices inspired by testimonial and feminist pedagogies, I am working to help my students not just learn about other perspectives and experiences, but learn to read literature in a way that does not ultimately sustain the perspectives and practices of white supremacy.

What is a “Navigational Log”?

The “Navigational Log” is an account of a student’s journey with a text. I playfully came up with the title in the context of a course on travel and migration literature, but the name has lived on as the assignment has migrated to other courses.

The Navigational Log scaffolds literary analysis in two parts: a double-entry journal and a close reading, or what I call “breadth” section and “depth” section. For the focus of each Log, I ask students to choose one of the 3 or 4 texts we’ve covered during a certain period of time. I know that it’s not feasible for my students to carefully and deeply read every text that goes on the syllabus; this approach helps me feel assured that my students are engaging very closely with at least some of the texts because it builds on the choices they’re already making about how they approach their assignments and manage their time.

My students are responsible for completing four Navigational Logs over the course of the semester. Repeating the assignment is important for giving them time to practice and develop the skills it asks of them – and it allows both me and them to see their growth very clearly.

Building confidence in their thinking with the “breadth” section

For the double-entry journal – or, “breadth” section, I ask students to choose 4-5 moments from across a text (be it a novel, a poem, a film, etc) and purposefully respond to those moments through different modes of literary thinking. This section requires that my students slow down in their reading, then sit with and process their ideas. The prompts give them guidance as to how they can find entry points for developing their ideas. For each “entry,” I invite them to:

• Identify a pattern or theme

• Closely examine and extrapolate on a notable image or word choice

• Look up and provide more information on a person, place, or event that’s mentioned in the text.

• Draw a connection to something that’s happening in the world.

• Draw a connection to another text they’ve read (in our class or elsewhere).

• Draw a connection between the text and their own experience.

• Write out a question they have about a text and provide one possible answer.

An important part of what I assess them on in this section – especially early on in the semester – is the extent to which they are experimenting with different kinds of approaches. In other words, if I see that they have written five entries drawing a connection between the text and their lives, I give them feedback that encourages them to try different approaches alongside the one that they’re most comfortable with. I do this because I want them to explore how there are different entry points into literary analysis and critical thinking – all valid, and all with the potential to unlock something important and unexpected about a text.

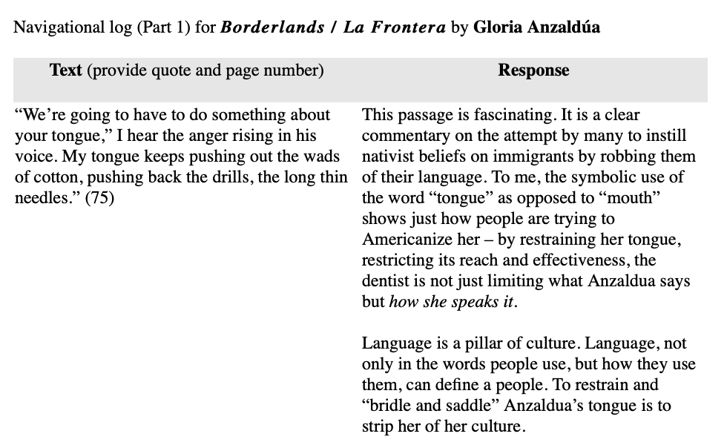

Image description: an example of a single “breadth entry” response to Borderlands/La Frontera by Gloria Anzaldúa. This entry illustrates an example of a student looking closely at a particular word choice and extrapolating on its importance for understanding the text – and its author – as a whole.

Image description: an example of a single “breadth entry” response to Signs Preceding the End of the World by Yuri Herrera. This entry illustrates a rather striking example of a student using the space of the response to articulate and process their own moral dilemma. In my feedback to this student, I encouraged them to think of “patriotism” as the very act of nuanced reflection and critical questioning that they were displaying in their response.

Image description: an example of a single “breadth entry” response to “Broken English Dream” by Pedro Pietri. This entry illustrates how a student is elaborating on something striking about the form of the poem and connecting it to their own experience as a migrant to the U.S.

When I teach students how to do response entries, I provide them with a blank template to work from and examples from some of my previous classes. We spend some time looking at these examples together: I ask them to make observations about the ways they see students responding to the texts. I purposefully choose examples addressing works they haven’t read yet, so that they focus on the approach rather than the content. I have them do some partner-based practice with drafting their own “log entries” and helping each other think of ways they might develop them in more depth.

Usually, by the end of the semester my students weave together multiple approaches and insights in a single response. My sense is that the time they spent being purposeful and varied with their entries helps them develop the confidence (and cognizance) to do so.

Making the jump from “responding” to close reading

Shifting into writing a more formal close reading can be one of the trickiest pieces of this assignment for students. If they are new to close reading (which the vast majority of my students are), their first instinct is to do a longer version of the kind of open response I ask of them in the “breadth” section. Thus, I provide additional guidance and practice with structuring a close reading and making the shift from observing and responding to crafting an argument. Sometimes my students choose to build on and formalize one of their “breadth entries;” sometimes they’ve saved addressing a section of the text specifically for the close reading.

One of the most effective approaches I’ve employed is collaborative close reading (See Danica Savonick’s amazing step-by-step guide). I also provide them with a close reading protocol and sentence-by-sentence example of a close reading paragraph.

Assessment and feedback

As an assessment tool for my course, the Log provides me with insight into how students are approaching their literary thinking in a way that a “reading quiz” can’t. It gives me a launching point to have a conversation with a student (through my written feedback or in person) about the way I see them approaching textual analysis, and allows me to really pinpoint where they may be getting stuck. I can also address common issues in a more precise way in class, with everyone. The Log has been particularly valuable for gaining insight on my quieter students who don’t rehearse their ideas aloud in class.

I grade students on a rubric with the following evaluative categories:

SUCCESSFUL NAVIGATIONAL LOGS WILL:

1. Have a “breadth” section that:

a. demonstrates a variety of approaches to literary thinking (questioning, connecting, close word analysis, etc.). (2 points)

b. are developed with some depth. (2 points)

c. are balanced from across the text (from the beginning, middle, and end). (1 point)

2. Have a “depth” section (a close reading) that:

a. Focuses on analyzing a single passage, poem, frame, screenshot or scene from the text to illuminate something about the work as a whole. (2 points)

b. has a thesis that focuses on the importance of a single feature (stylistic or formal) of that passage, and is supported by evidence that helps to illustrate its effect. (2 points)

c. is organized in a manner that effectively showcases the argument. (1 point)

Breaking up the rubric in this way helps me focus my feedback as much as it helps them see the different components of the skills they are practicing. In order to save time and still provide students with meaningful feedback on their logs, I keep a running word document of my comments and use them either as direct repeats or as a basis from which I can tweak my feedback. My current school also uses a learning management system that saves comments I write in particular sections of the assignment’s rubric, allowing me to easily repeat and tweak comments for other students’ feedback.

I have found that it is helpful to review examples with students again, in class, after I’ve provided them with feedback on their first Logs. If, after two rounds of Logs, I see that a student is still struggling with the assignment, I ask them to meet with me to talk it through. Usually, after about a 15 minute tutorial, whatever hasn’t yet clicked for them about the assignment falls into place.

Results – keeping the long haul of anti-racist work in our sights

Many of my students have reported that although the Logs take a lot of time, they enjoy doing them and can see the impact their work on them was making in their comfort level with writing and talking about literature. It’s amazing to see my students consistently improve over the course of the semester (even when that semester suddenly requires us all to pivot from face-to-face learning to remote learning!). On paper, I see the improvement of their written abilities in critical analysis and close reading. More informally, yet consistently, I see the impact these Logs make on in the way my students engage in our whole-class and small-group discussions on our textual material – material that has them encountering the perspectives of others, accounts of physical and structural violence, colonial histories and its racial capitalist legacies. When my students purposefully work through this material in a recurring and sustained manner (guided by the individual “conversations” I am able to have with them through their Logs), I see them gain more confidence to trust and voice the complexities of their thoughts and experiences with their colleagues, to invest time in developing a nuanced conversation by drawing from a shared text and listening to one another, to ask probing questions of, and make crucial connections to, our world.

For those of us who benefit from the structures of heteronormative white supremacy, doing antiracist work is not something we can “achieve” and then add to our resume. Being an antiracist ally, accomplice, or collaborator is not an accolade that we acquire and then add to our email signatures: it is a daily choice made by moment-to-moment efforts and actions requiring reflective, imaginative, and communicative skills that must be learned and practiced like anything else. The Navigational Log is one tool that has made a difference for my students in shaking off the standardized, check-box-oriented learning practices that ultimately sustain white supremacy. It is not a “cure-all” or magic formula for ending racism tomorrow; one semester of building these skills does not undo years of training that they’ve been forced to adopt in their educational careers thus far. However, when I witness my students rehearsing the skills required of sustained antiracist work, I feel hopeful that literature and its study can equip them for the long task of building an antiracist future.

APPENDIX:

Assignment sheet and “Breadth Entry” template

Handout: Key Steps of Close Reading

Handout: How to Organize a Paragraph of Close Reading

Sample Navigational Log on Nuyorican Poetry

Sample Navigational Log on Yaa Gyasi’s novel Homegoing

Sample Navigational Log on Star Trek: The Next Generation – Season 5, Episode 2 “Darmok”