Why did you apply to HASTAC?

HASTAC’s accessible, welcoming, and intentional approach drew me to apply as I looked beyond my institution for further opportunities to meet other early career researchers who value collaborative cross-disciplinary research. My work at Carnegie Mellon has ranged from learning with labor activists to designing and delivering accessible educational materials on artificial intelligence with robotics researchers. I started as a HASTAC Scholar while entering my “dissertating” phase of the PhD program, hoping to engage with a community of emerging scholars across disciplines and fields. All in all, I find that my scholarship is stronger, and the process of researching is more enjoyable when developed in conversation with others. I have found HASTAC to be a great space for this.

What has been your favorite course so far as an instructor or student? Why?

My favorite course as a graduate student has been “Major Fiction Then and Now: Imagining the World,” taught by Jeffrey J. Williams through the Carnegie Mellon University Prison Education Project. The course follows the Inside-Out model of prison education, bringing Carnegie Mellon students, undergrad and grad, inside and out, together each week for in-person instruction inside the correctional facility. The course traced major works of fiction – classic texts like Mrs. Dalloway and Black No More alongside more contemporary books like Kindred and Station Eleven. The course forced me to rethink my relationship to fiction and I learned so much from my fellow inside classmates.

What do you hope to accomplish with your research or teaching?

In my research, I primarily study activist and queer feminist media infrastructures. In my dissertation, for instance, I am interested in tracing how lesbian feminist identity coalesced across forms, modes, and channels in the United States to foster a shared sense of feminist mobility and identity. In my work curating and processing archives, I am committed to preserving and making accessible working-class activist papers, which are often obscured in the larger frame of the archive. In a collection I am currently co-editing on drag and celebrity, I am focused on recentering the types of drag happening in local communities and building a teachable collection that brings together practitioners, scholars, and community members. Across all these projects and my future work, I hope to produce accessible research on activist cultures and center the often overlooked materials that contribute to building and maintaining the richness of these communities.

In my classes, I employ feminist pedagogy and aim to empower students in their learning processes. This includes addressing power in the classroom outright as we build a set of discussion expectations together, incorporating meaningful reflection and collaboration that moves beyond transactional assignments, and intentionally teaching content that centers historically marginalized voices. In the first-year writing classroom specifically, I hope to complicate student’s understanding of “high” culture by incorporating a variety of cultural forms – from graphic novels to activist protest signs – as objects of study. By the end of the course, students are not only able to manage their writing processes, but they are stronger critical thinkers when it comes to the media they consume and produce.

How does digital scholarship fit into your research or teaching?

Currently, I am proud to be a part of a team of scholars and community members dedicated to telling the story of working-class activist Kipp Dawson. Kipp Dawson is an activist, retired coal miner, and middle-school teacher who has built coalitions for over 60 years on the front lines of the Civil Rights Movement, Vietnam anti-war movement, women’s movement, gay liberation movement, labor movement, and education justice movement. In 2021 and 2022, I helped process her massive archival collection, known today as the Kipp Dawson Papers housed at the University of Pittsburgh Archives and Special Collections. Now, the website https://kippdawson.com/ brings some of these materials from her decades of committed work into digital story maps and accessible, dynamic pages. I love seeing the ways archives can be expanded and made into accessible teaching tools, and I use the website regularly in the classroom as an introduction to archival work and activist cultures in the first-year writing classroom.

Catherine, Kipp, and Dr. Jessie Ramey celebrating the Kipp Dawson Paper’s opening to the public at the University of Pittsburgh in October 2022.

What’s something that people would be surprised to know about you?

Folks always seem shocked to learn I grew up in rural Pennsylvania surrounded by cows, ducks, and collies. Classism within the academy is still very real, and the often-imagined doctoral student at Carnegie Mellon is not necessarily a rural, working-class woman. When I say where I am from (Clearfield, PA) I normally get blank stares until I add an academic point of reference (Penn State is about 45 minutes from there). Growing up with a strong community of working-class rural women, many of whose stories will most likely never be told, informs my drive to work on everyday feminist media and culture. This said, I do love returning to the area, and it is not a coincidence that I love spending time outdoors. (Bilger’s Rocks is one of the best-kept hidden gems in the area.)

What are some things that you wish you had known before you got into graduate school?

As someone who didn’t know anyone with a doctorate, let alone someone with a PhD in Literary and Cultural Studies growing up, I wish I had known the current state of the humanities in higher education. Tenure-track lines are disappearing left and right, programs across the country are halting admission, and there is a very real tension between STEM and the humanities as departments fight for funding. This landscape is part of why groups like HASTAC are so important.

The current state would not change my decision to pursue a PhD, but I did not anticipate I would constantly have to rearticulate the value of my degree to peers, mentors, and the general public. I will continue to fight for funding for the humanities at the departmental, institutional, and national levels. For me, this involves working with fellow graduate students on the department level to make sure the needs of our most vulnerable students are addressed. On the national level, this involves advocating for increased funding to the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Archives and Records Administration on Capitol Hill with the National Humanities Alliance. This type of work is not what I imagined the graduate student job would entail. So, in short, I would tell past me: Your research is not only valid but important and so is your advocacy.

What do you want to do after you graduate?

I hope to continue working on preserving and sharing the stories of working-class and queer activists. Working with Kipp has been the most inspiring and meaningful project I have undertaken during my time in the PhD. I aim to continue collaborating with her, and other changemakers like her, in the archives and beyond. I also plan to continue teaching in some capacity, either at the collegiate level or in a nontraditional space. I still believe bell hooks’ suggestion that even “with all its limitations [the classroom] remains a location of possibility” and foresee myself in that space (hooks, 1994: 207).

How do you envision HASTAC and higher education in 10 years? Where do you fit in?

I imagine HASTAC at the forefront of cultivating cross-disciplinary partnerships and continuing to build the next generation of scholars, leaders, and teachers. With rapid changes happening in higher education, I hope that cultural studies, gender and sexuality studies, and literary studies are institutionally protected. I picture myself and my work contributing to these areas of study by continuing to work on projects across the humanities, arts, and sciences. One possible approach I plan to take is to work toward making archives more accessible, equitable, and just. I don’t want to romanticize archives as they are fraught spaces with contested and sometimes outright violent histories. Still, I do think they have radical potential for preserving and connecting communities across generations in the future. I see how impactful Kipp’s archive has already been in fostering intergenerational conversation and envision a future where even more collections like hers exist and engage the general public.

What are you currently reading, watching, or listening to?

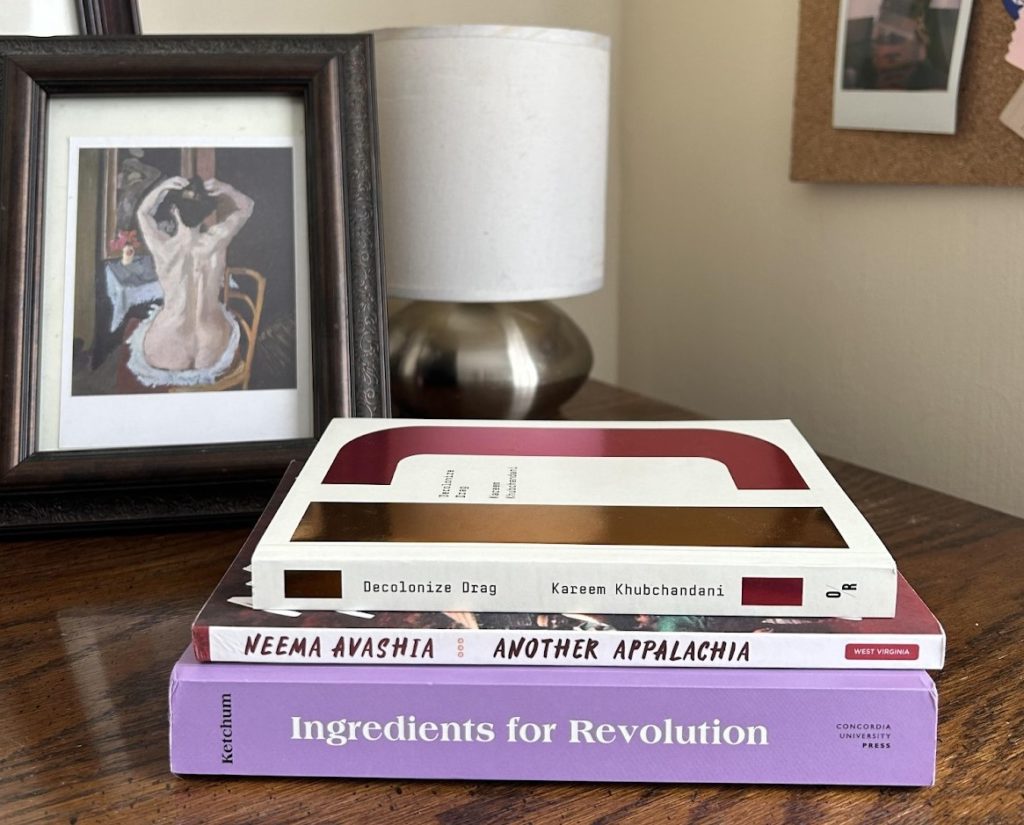

Currently, I’m reading Alex Ketchum’s Ingredients for Revolution: A History of American Feminist Restaurants, Cafes, and Coffeehouses, Neema Avashia’s Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place, and Kareem Khubchandani’s Decolonize Drag.

My desk as of March 20th, 2024.

You can connect with Catherine via email caevans@andrew.cmu.edu or via Twitter (X) @caevans32.