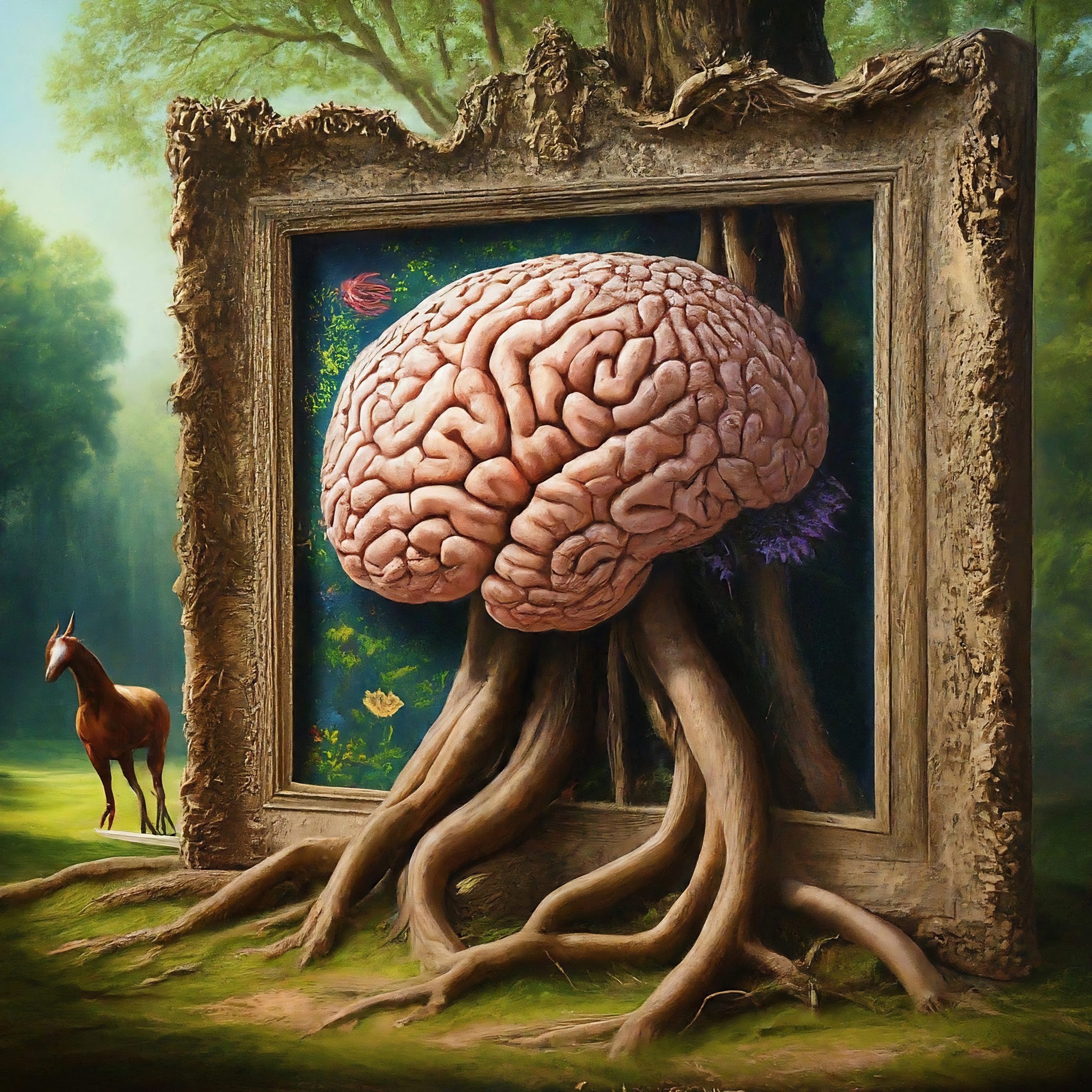

Trompe-l’oeil by Mechelle Gilford and Sir Bard circa 2024

The Art of Unseeing: How CVI Rewrites Aesthetics

We tend to presume a universal experience of art – those transcendent moments when a masterpiece resonates with some immutable inner truth. Perhaps we cling to this notion, a byproduct of cultural conditioning, seeking a shared language of beauty. Yet, for children with Cortical Visual Impairment (CVI), the very pathway between perception and aesthetic experience is fundamentally altered. Could theirs be the truer vision, uncluttered by our preconceived notions of how art should be experienced?

Imagine looking at the world through a kaleidoscope in constant flux, where familiar objects shift and fragment into a disorienting dance of colors and shapes. What was once recognizable dissolves into an abstract composition. Movement becomes a blur. This is the reality for those with CVI, a disruption in how the brain processes visual information. Yet, even amidst this visual instability lies an undeniable human impulse to see, to find patterns, and create meaning.

This drive leads us to neuroaesthetics, the field exploring the biological basis of our response to art. While traditional research focuses on “typical” visual pathways, the study of children with CVI offers a startling counterpoint. Using brain imaging, researchers witness a paradox: Areas of the brain associated with visual processing still show activity in response to color, light, and even simple patterns, despite the child’s limited functional vision. This discovery isn’t mere scientific curiosity; it speaks to the resilience of the human spirit. Children with CVI often display an unexpected fascination with bright hues, bold shapes, or even flickering lights. Art, in its purest form, becomes an exploration of the most fundamental visual elements – a sensory experience rather than an exercise in representational mastery.

The implications of these findings extend far beyond the hushed halls of museums. They ripple outwards, reshaping our understanding of visual experience, its connection to aesthetics, and highlighting the remarkable adaptability of the human brain. This knowledge underscores the brain’s neuroplasticity, its ability to change and reorganize itself. This empowers teachers with a profound new perspective. Simple high-contrast patterns, previously seen as purely educational aids, can now be harnessed as powerful tools to stimulate the brain and unlock gateways to aesthetic wonder.

This newfound understanding of CVI can also serve as a potent lens through which we can approach Universal Design. Architects can reimagine their craft, creating spaces that are accessible to not just those with CVI, but a broader range of individuals. Clear lines and uncluttered layouts promote ease of navigation for everyone, while color transcends mere decoration, becoming a crucial navigational tool. Strategically placed hues can guide movement and foster a sense of spatial awareness, benefiting users with and without CVI.

Intriguingly, artificial intelligence could revolutionize our understanding of these processes. Could AI help us decode these intriguing brain responses? Its ability to analyze complex brain scans has the potential to reveal subtle patterns of activity that might be invisible to the human eye, offering profound insights into how the brain constructs a sense of beauty, even with atypical visual processing. AI’s ability to generate countless visual variations could become a powerful research tool, exposing individuals with CVI to a vast array of visuals to pinpoint what consistently elicits strong responses. The insights gleaned from such analysis could pave the way for the development of personalized therapeutic tools. Imagine AI-generated visual experiences with the potential to stimulate and strengthen the visual pathways in a child with CVI – a digital complement to traditional therapies, opening up new avenues for progress.

Of course, beauty, like the brains we perceive it with, remains elusive. CVI highlights the incredible flexibility of the human mind in finding meaning and aesthetic delight. For some children, the shifting colors of a disco ball hold the same enchantment as sunlight filtering through fractured stained glass. This challenges us to reconsider our definitions of “valid” artistic experiences and raises a profound question: Could a deeper understanding of the neurology behind CVI lead us not to a single, revised definition of beauty, but rather to the realization that the search for a universal definition is perhaps the most quixotic artistic endeavor of all?