This is the second post in a series leading up to my HASTAC webinar “From Cardi B to Stranger Things: Using Popular Culture in the Writing Classroom.” Circulation Studies is something I am relatively new to, but considering the speed at which popular culture is shared and re-shared, it makes sense to incorporate discussion of circulation in the first year writing classroom. There is a tension between intention and uptake, and while many students are familiar with old posts resurfacing and reactionary politics on twitter, there is room for delving more into the circulation and re-purposing of our texts as a consideration in our actual composing. It is not just about “what we meant” but rather “what the uptakes might be” and “how this might be re-used.” The internet is written in ink, sure, but it is also constantly photocopied. What is interesting about these stances on circulation is that it provides space for students to reconsider our conceptions of audience – not only our intended audience but the far more unintended audiences we can consider.

Origin: Rhetorical Velocity and Consequentialism

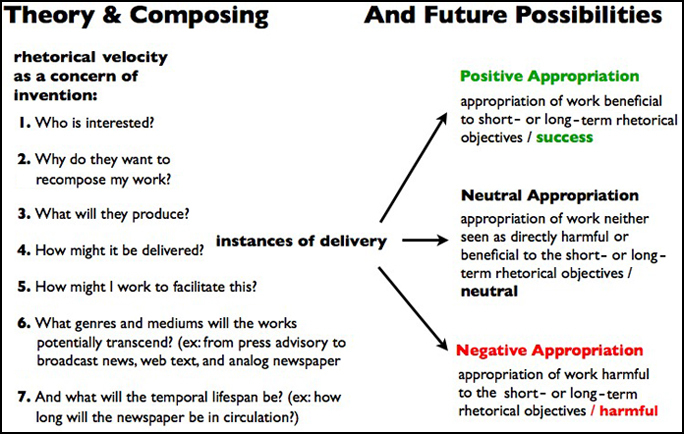

Early on in my program, I was introduced to Jim Rodolfo‘s work, notably his work with Danielle DeVoss on rhetorical velocity or how writers can anticipate the recomposition of their texts. While Ridolofo and Devoss stress the positive, neutral, and negative appropriations of texts as they are repurposed and recirculated (i.e. thinking about the potential ways our writing can/will be re-contextualized, re-composed, and re-circulated by others for their own rhetorical purposes) and the speed by which texts “travel,” rhetorical velocity also asks writers to consider many more potential audiences when composing.

Figure 1. Chart of Considerations for Rhetorical Velocity taken from Ridolfo and DeVoss’s Kairos article, “Composing for Re-Composition: Rhetorical Velocity and Delivery.”

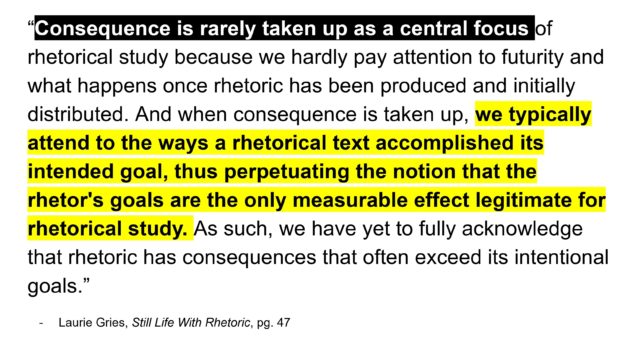

As I have moved into my dissertation research, I have taken notice of Laurie Gries’s work with the circulation of the Obama Hope image in her Still Life With Rhetoric. Drawing from Kevin Porter‘s concept of consequentialism, Gries explores something important about the ways we tend to favor and attend to a writer’s intentions for their writing over its eventual uptake (something her work will address):

Consequence is rarely taken up as a central focus…we typically attend to the ways a rhetorical text accomplished its intended goal, thus perpetuating the notion that the rhetor’s goals are the only measurable effect legitimate for rhetorical study. As such, we have yet to fully acknowledge that rhetoric has consequences that often exceed its intentional goals. (47)

With the ease and speed at which we circulate texts online–spread memes, tweets, and posts on social media–an eye towards these uptakes marks an important opportunity to help students see the larger information ecosystem they are entangled within and the ways this shapes what they have access to. Circulation opens space to revisit ideas of information literacy, bias/spin, and journalistic integrity when it comes to news stories. It also asks that we consider what something like “trending” means when the seemingly nonsensical things (i.e. the Kardashians) receive absurd amounts of exposure over actual news we should be attending to (i. e. national events).

Using Tweets to Teach Information Literacy

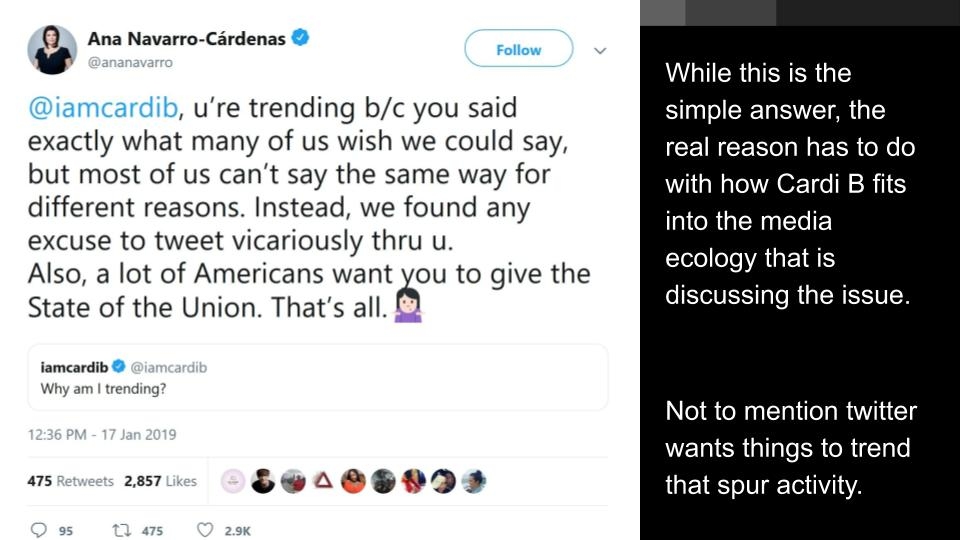

For this lesson I saved a series of tweets pertaining to one of Cardi B’s 2019 Instagram video critiquing the Trump Administration, tweets that were uptaken and repurposed by members of Congress. As seen in the slideshow below, both the original tweet and responses from politicians and political pundits, all of which provides helpful context as to why she was trending. What I emphasize (especially in the last slide below) is that trending is not about someone articulating a truth to power for others that do not have a voice; trending is an algorithmic process that amplifies and circulates content (tweets in this case) that will spur more activity from users. While the writer’s intentions might at times align with the platform algorithms’ directive to spur activity, trending is always concerned with the algorithms’ priorities over the human writers’ intentions.

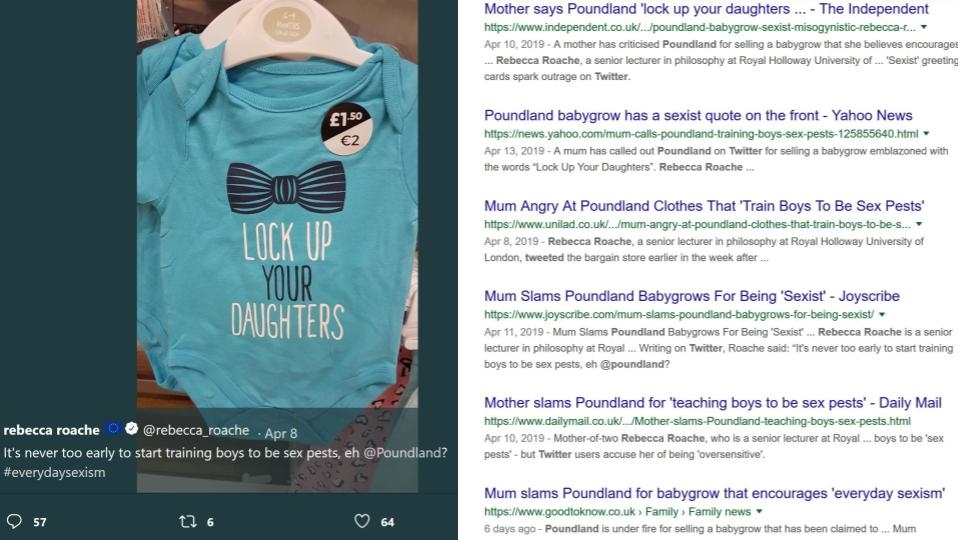

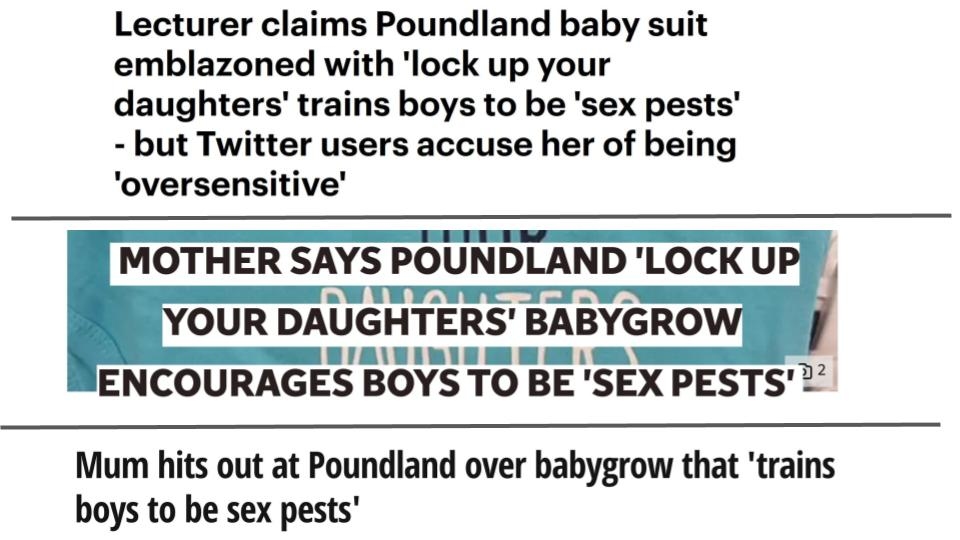

From this illustrative example we can examine the ways that writers re-purpose texts to seize multiple audiences’ attention (both human and algorithmic). To this end, I also chose a series of “news” stories generated from yet another tweet; this time from a mother (who happens to be a professor) critiquing the British retail chain Poundland. What is important about this second set of artifacts is that most of them are glorified “re-posts” of an original piece, complete with their own biases/spins and attention grabbing headlines.

I ask students to investigate each article to try and figure which one was the original interviewer of the Poundland twitter critic. I also ask students to notice the differences in the headlines and to question how this shapes how they read the story (how these headlines prime their interpretation). For example, why does one news headline bring up her occupation as a lecturer? What relevance does this have? What larger discussions/tensions are they pointing to in doing so? And why might they do this? Just like the algorithms from the Cardi B example, these “news stories” (some of which are borderline tabloids) are meant to drive traffic to their respective sites quickly (these sites too are chasing eyeballs for advertising dollars, just like social media algorithms).

I also have student pay attention to sourcing: which stories provide direct quotations, which provide useful contextual information, and which mention where their quotes/ideas come from (good journalistic practices). Once they have to look for it, students are often surprised that a lot of what is trying to pass as “journalism” here is actually poorly sourced, factually inaccurate, and laced with plenty of spin. As we consider the intentions of the respective publications, I ask students to think about what might have happened to our original tweeter (in reality, she was harassed by the usual trolling suspects) and to consider whether or not her intentions justify any of the potential consequences her tweet generated for her (not to mention the culpability of the publications who have profited from and caused her subsequent harassment). Not to mention considering what her original purpose and intended audience for this tweet is meant to be (a group of friends on twitter) compared to how some publications disingenuously contextualized her tweet (a lecturer forcing their beliefs on the public sphere).

As part of the activity has students using their news source evaluating skills to identify which “article” is the original, you can use any series of news stories for this second set (this re-purposing of news stories is a common practice). Alternatively, you can select news stories from drastically different sources (with very obvious and different ideological leanings) about the same event and then have students try to figure which publication it came from (provide them only the headline and text for the news stories, no author names or images). In addition to some information and media literacy, this lesson is meant to help students understand the material consequences of our social media re-composing and to re-discover the importance of context in accurately assessing information. Students can see that circulation is about far more than obtaining information, it also concerns how ideas and texts spread, respond, remix, and combine with other ideas and texts. Moreover, they can see how social media platforms generate revenue by mediating our circulation practices and brokering the data we generate in doing so to advertisers.

The Lesson Plan

NOTE: I co-developed this second lesson with another student from my program. While it possible to complete a variation of this lesson with printouts, the ability to visit the actual webpages live makes this lesson more suitable for classrooms where students have internet access (via computers or smart devices).

Necessary Components: 3-5 News Articles from different news sources concerning the same Topic (should of varying journalistic quality).

Activity Procedure: In small groups (2-3 people) work through the news stories to figure out: which one was the original, the credentials of the author, the positive and/or negative “spin” each story brings, and what evidence it presents (direct quotations/paraphrases, source identification, contextual information, images, etc).

Variation: Pull all of the text out of the articles (headlines and body, no images) and copy them into a word document that does not identify the source or the author. Present students with the list of publications the news stories came from and have them identify which story came from which publication.

Gries, Laurie E. Still Life with Rhetoric: A New Materialist Approach for Visual Rhetorics. Utah State University Press, 2015.

Ridolfo, Jim, & DeVoss, Dànielle Nicole. (2009). Composing for Recomposition: Rhetorical Velocity and Delivery. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 13(2). Retrieved March 27, 2020, from

http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/13.2/topoi/ridolfo_devoss/velocity.html