Image by Free-Photos from Pixabay

This post is the first in a series that relates to my HASTAC webinar “From Cardi B to Stranger Things: Using Popular Culture in the Writing Classroom.” In this post I explore intertextuality–how texts rely on other texts to make meaning–as an important way to help students work through the rhetorical implications and affordances of citation. I also understand that there are far more citational practices than just those encapsulated in MLA and APA stylistic preferences. Thinking of ethos as a relationship between a rhetor (writer, artist, speaker, thinker, etc) and an audience, intertextual references are one way that rhetors establish credibility with an audience: whether through honoring their influences, signaling shared knowledges, or building on previous ideas and circulating them, citations and references do a lot more than just supply quotations to meet assignment parameters.

Origins of an Idea

While taking Gwen Pough‘s Hip Hop Feminism course a couple of summers ago, I was assigned to present Treva Lindsey‘s article “Let Me Blow Your Mind – Hip Hop Feminist Futures in Theory and Praxis.” Lindsey argues for a hip hop feminist theoretical orientation that centers the experience of black girls as a way to ensure scholarship attends to those most at the margins. Her article offers many different threads in hip hop studies, and I find her discussion of Kyra Gaunt’s sonic narratives and lyrical narratives to be particularly interesting. As Lindsey challenges, “educators must care-fully consider how the sonic simultaneously functions as an interwoven, but distinct narrative within hip-hop music” (62). Lindsey also argues for a distinction between what a song communicates with its beats and what it communicates with its lyrics, and she provokes an interesting question: Can you like rap music without inadvertently supporting the sexism in it?

Regardless, these two kinds of narratives (sonic and lyrical) help to explain some of the ways rap songs are able to stack information from multiple sources into one composition–not unlike how Emery Petchauer describes Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” as an example of a song that “[communicates] a great deal of information in a short period of time” (81). Rappers sample lyrics, sound bytes, and beats, each specifically and purposely chosen. Often times sampling is far from “random,” the beat has to be good, but many hip hop artists strategically sample other artists for various reasons: to honor their inspirations and influences, to borrow the reputation/credibility (ethos) of artists they respect, and/or to reference ideas they want their work to enter into conversation with. When it came to teaching intermediate research writing, I realized these were the same goals I had for my students. So, I started to pay better attention to the complex moves artists like (among many many many others) Lauryn Hill, Kendrick Lamar, Queen Latifah, and Jay-Z demonstrated in their songs, this layering of references adding a completely new dimension to my thinking about their songs.

Using Music to Teach Citation

For this lesson there are two important websites: Who Sampled? for discovering the sonic narrative of a song and Genius for unpacking the lyrical narrative.

Who Sampled is a website that functions as a searchable database for all of the various connections between songs, not only artists who are sampling each other, but also songs that have been covered and remixed. What is nice about this site is that it lists all the samples an artist used in their song in addition to who sampled their song in their own. Clicking on sample brings up two audio streams, one from the song you are “researching” and one from the original song that it sampled.

Genius is a website that provides the lyrics to various songs. What is unique about it is that users can provide annotations, comments that appear on a sidebar and which the more thorough users can provide links to “evidence” and “sources” for their claims. Even more interesting is that the artists themselves can provide annotations (these comments are demarcated differently).

I designed this lesson to help students understand what I saw as complex and important citational practices layered into these songs; practices less about formality or standards and more about adding an additional layer of meaning to writing. What better goal for intermediate research writing? Artists include references in both their lyrics and their beats. I see a song’s lyrical narrative (literally the lyrics of the song) as an opportunity to engage in some close-reading. These references are a little easier to unpack as there is specific text to point to. A song’s sonic narrative (the songs it samples) is looking at the ideas, figures, and intertextual connections that the artist is referencing through their sampling of other artists. As with scholarly citations in a research paper, artists sample for various reasons, and short of asking the artists directly, unearthing connections takes a little more digging. I have students look up these other songs sampled in the sonic narrative. They dig through the lyrics, look up information on these other artists, and also the social, cultural, and historical context the song is situated in; anything that gives us more insight into why the song might have been sampled.

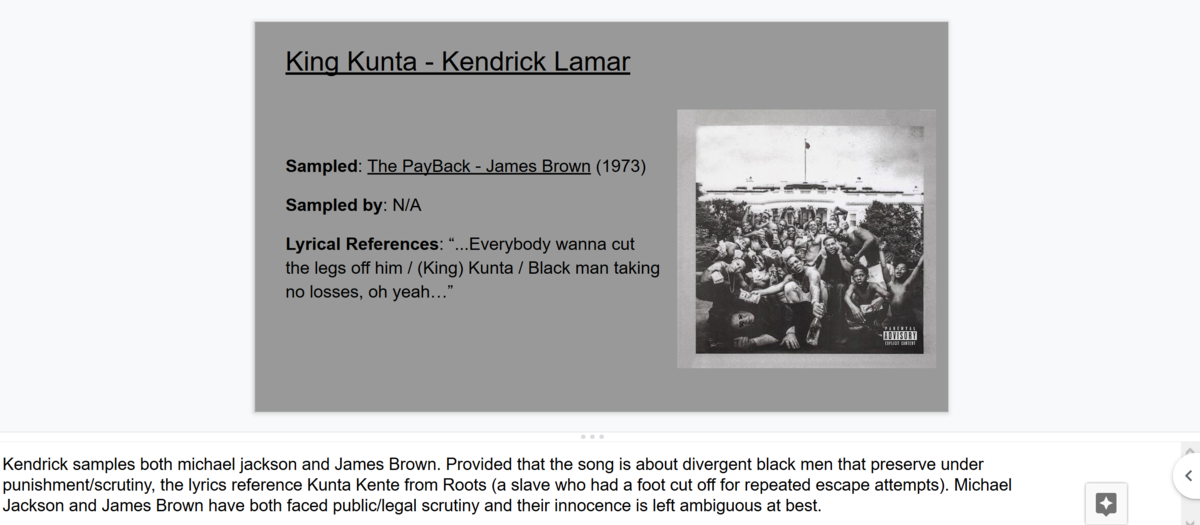

Students find out things like that Kendrick Lamar samples James Brown’s “The Payback” in his “King Kunta” not just because Brown is a major influence on Kendrick (not to mention being the “Godfather of Soul”), but also because Brown’s song engaged with similar ideas about the defamation of black artist’s by the media at the height of their fame. Or that Queen Latifah’s 1993 rap song “U.N.I.T.Y.” samples lyrics from reggae-artist Desmond Dekker’s 1968 song “Unity” which advocated for solidarity amongst men and women in the black community and to which Latifah’s song rebukes men not living up to this standard.

More than just an analog for academic research, examining sonic and lyrical narratives as citational practices helps students to consider writing’s inherent intertextuality. I ask students to reconsider what we do when we cite and how ideas rely on and build from other ideas (and that this is a good thing). Students come to understand that when they do research, they aren’t just finding sources and placing them into papers, but rather they are entering ongoing conversations situated in communities. These communities expect students to demonstrate their familiarity with ideas and knowledge important to that community. Research is about backing up their claims, yes, but it is also about identifying influences and entering into a conversation with them. In their own right, citations can be a handy shortcut for conducting research–in the same way that hip hop artists embed and circulate ideas in their sonic and lyrical narratives, so too do scholars embed and circulate ideas in their works cited pages and prose.

The Lesson Plan

NOTE: This lesson will require a device with internet access, preferably a computer in order to access both Genius and Who Sampled? but also to create a slide for their chosen song. Students will create a single slide to add to an aggregate class presentation. While in this example I provided students with a list to choose from, pre-selected songs that have interesting sonic narratives to dig through, I also have taught this lesson with students selecting their own songs. As it stands, this lesson can acts as a good “class demonstration” with students choosing their own songs for a similar homework assignment.

Working in small groups of 2-3 people, choose a song from the following list and look it up on both Genius and Who Sampled?:

- “Bring the Noise” – Public Enemy

- “99 Problems” – Jay-Z

- “Doo Wop (That Thing)” – Lauryn Hill

- “U.N.I.T.Y.” – Queen Latifah

- “Paper Planes” – M.I.A.

- “Straight Outta Compton” – N.W.A.

- “Dirty Harry” – The Gorillaz

As a group create a slide to share with the class that includes the following information/features:

- Name of the Song and the Artist

- 1-2 Lyrical References

- 1-2 Songs the song samples

- An image(s) that represent the song (i.e. picture of the artist, album cover, etc).

- In the comments section: Write 1 paragraph that connects and explains how the lyrical narrative and sonic narrative outlined above contribute to the meaning of the song and/or explains “why” the artist makes the lyrical and sonic references (sampling) that they do.

Works Cited:

Lindsey, Treva B. “Let Me Blow Your Mind: Hip Hop Feminist Futures in Theory and Praxis.” Urban Education, vol. 50, no. 1, 2015, pp. 52-77.

Petchauer, Emery. “I Look at Hip-Hop as a Philosophy: Edutainment, Sampling, and Classroom Practices.” Hip-Hop Culture in College Students’ Lives: Elements, Embodiment, and Higher Edutainment. Routledge, 2011, pp. 71-88.