Written in conversation with George Hoagland.

The Problem I Made for Myself

Last September I found myself for the first time in a very long time teaching (and grading) a large enrollment course. Well, large for me: about 60 students in one class and another of about 30. Even in these bigger-than-seminar classes, I am really there for the weekly, short, low-stakes writing assignments. I trust that it is one of the best thinking and learning practices around, and it is satisfying when each student builds a rocking body of critical work over the semester. Students at first hate the workload and then by the midterm they see how it is working, and by end of the semester they are invariably impressed with themselves for all that writing.

From Liberal Arts to Bigger than Liberal Arts

I’ve spent the bulk of my teaching years in small Liberal Arts-style seminar classes, so I’ve formed most of my pedagogical habits in this context — usually 2 or 3 courses per semester with under 20 students per course, so usually a max of 50 students total for all courses, usually far fewer. So that’s when I built all this trust for weekly writing assignments.

So, even though I did the math last September and knew that it would mean reading and responding to around 90 one-page assignments per week, I put my weekly Keyword Portfolio assignment on both syllabi, making each one-pager worth 2% of the final grade, with the full portfolio worth 20%. And I put the whole thing up on Blackboard and made all of the stressed-out students turn them in.

Reader, I didn’t grade them.

I put the assignment up on Blackboard and registered the Points Possible, thinking I would just hammer out fast little grades each week after class. But I never did. First of all, who does anything beside eat a snack directly after class? Not me. Second of all, there is a reason why therapists tell you there is no such thing as “just” doing anything. I found it impossible to “just” or even justly grade these “low-stakes” assignments.

It turns out that I was so stressed out by so many fast little grades (is it a 1.25/2 or a 1.5/2 and why??), that I could never even get them started, so by mid-semester I had hundreds of weekly assignments to read and respond to and students in near revolt. After all of the time I spent convincing students that these assignments were no big thing, I was sending the opposite message since clearly my grading problem was a real big thing.

Around mid-semester I happened to mention my grading crisis to my friend and colleague, the brilliant Anthropologist Natasha Myers at York University, and she told me about her non-numeric, descriptive rubric, in which students can track their improvement and how to improve, and, as she put it, “improvement is what is counts for the final grade.” Totally agreed. So starting last term, I put together my own non-numeric rubric.

Look What the Grading Languages Dragged In

But then came the problem of figuring out what words I would use for my descriptive rubric. I am obsessed with the ways that our default grading/evaluation languages are often ableist (strong//weak, awkward) or classist (rich, elegant//poor) and so I’m always looking for better ways to communicate “excellence” or “needs-work.” I also found that students have a hard time not personalizing “satisfactory” and “unsatisfactory” — making these assessments less about the work they turned in and more about who they are as people.

And The Rest is Rubric

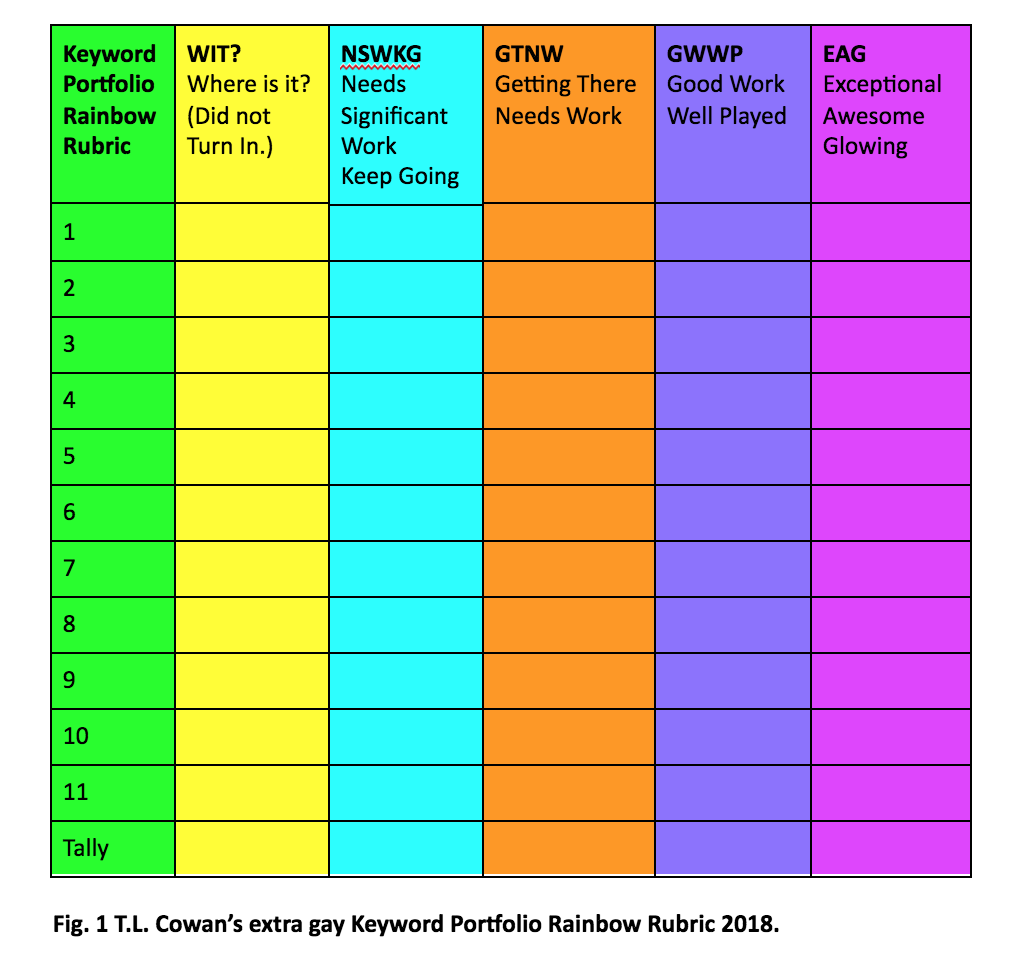

So, with all of this in mind… 1) to help myself grade faster and better, 2) to reflect my desire for these weekly writing assignments to help students improve their academic writing 3) as well as demonstrate they have done the week’s readings, 4) while not reproducing some of the punitive and/or stigmatizing languages we normalize in the academy… I came up with this rubric:

EAG – Exceptional Awesome Glowing – thoughtful and careful reading, writing and critical analysis; deals with the complexities of the reading/s and demonstrates a rigorous and creative capacity with the key idea/s; this is some polished, shiny work! Come see me to discuss.

GWWP – Good Work Well-Played; meets all elements of the assignment and demonstrates a clear understanding of the material; substantial engagement with the complexities of the material; but not quite polished all the way. Come see me to discuss.

GTNW – Getting There Needs Work – is getting the basic idea, but is not engaging with complexity; needs at least one element of the assignment to be improved. Come see me to discuss.

NSWKG – Needs Significant Work Keep Going- submitted the work, but it’s not fulfilling the terms of the assignment; needs multiple elements to be improved; did you read the assignment carefully? likely the student needs to pay more attention to the assignment details. Come see me to discuss.

WIT? – Where is it? (Did not turn in.)

Social Media and Pedagogy as Team Sport

Because I’m a pedagogy nerd, I started to write about all of above in a Facebook post. And because I’m friends with a lot of pedagogy nerds, I got the most amazing comments. In particular, my friend and FemTechNet comrade George Hoagland posted their truly fabulous rubric (see George’s linked post “How to do Grading With Words: Weekly Writing Assignments and Descriptive Rubrics (Part 2)”) and we started a conversation that we’ve now made public here on HASTAC.

Rubrics with Flair/Flare, Evaluation as Dialogue

George’s fabulous rubric, which uses grading as part of a larger project of building a “quality-affirming and skill-building universe,” makes me believe that this other teaching world is possible. Yes, George, exactly!

And, in addition to George’s rubric, the discussion that followed in the comments that day demonstrated the collective intelligence and experience of so many. For example, a senior colleague and trusted friend, Communication scholar Lisa Henderson suggested that we “put a web page not in a high-to-low column. Maybe in a sentence? Or a two-by-two (EA upper left, GW upper right, GTNW lower left, NSW lower right) or in a pinwheel = in motion! I always hate getting down to the D and F-range grades at the bottom of the list.” YES, Lisa. Of course. Let’s design these.

Thinking with Lisa’s suggestions, I came up with this weekly chart for the term to track how it’s going. With hesitation, I have made this chart into a rainbow situation. I’ve been so gay for so long, I’m ambivalent about the potentially queer imperialist power of the rainbow… I just needed to say that. But rainbows have a lot of power – we all know that – and this might be where we need one. For those of you who aren’t so gay and can’t imagine it… this is what a weekly Keyword Portfolio Rainbow Rubric might look like. BTW, there is no such thing as too gay. My personal style preference would be to go simple b & w. And as I write this I realize that in the future I’m going to give students a rainbow or b & w option. Some people really like colorful things. I’m getting a little off-topic. Style matters.

On ‘Pedagogical Amnesia’ or: “I already did this and then I forgot”

Teaching is funny, isn’t it? So often at the end of the term I forget things that happened that I want to do again. Is there such a thing as pedagogical amnesia? Once the term is over, it’s like it never existed, since for many years working in precarious positions, once a term was over, I never knew if I’d be back again. I’ve taught courses in several disciplines and moved institutions a few times (hello, adjunct methods). In each institution, in each discipline, I’ve developed some tricks. However, in my new job at UTSC, teaching these larger enrolment courses under pre-existing titles like “Media Ethics” and “Media & Work,” I got a bit stuck in the default Blackboard numbers are the only real thing infrastructure and forgot to make my own work-arounds/word-arounds.

For example, at both The New School and Yale I taught small seminars on Critical Disability Studies/Crip Theory, a course called “Assisted Living.” In these classes the students and I developed course-specific terms/acronyms for this kind of weekly writing rubric as a way to collectively re-think our evaluative languages and practices – to crip our evaluative practices. It was *extremely* fun and hilarious, and made grading way less stressful too.

So this September, I’m going to remember past teaching tricks and ask students what rubric would be useful and even motivating for them. Yes, I use class time to talk about the structure of the class. I know, right? So process-is-knowledge. This is also the semester that the University of Toronto is switching to a new Canvas-based LMS, so it means I will have to figure out another work-around for grading-with-words.

Riffing on George’s practice, I think these rubrics we develop with our students can help us to collectively come up with grading languages that are descriptive without reproducing ablest (strong/weak; awkward, etc.) and/or classist (rich/poor; elegant, sophisticated, etc.) language about student writing. They also move away from “satisfactory/unsatisfactory,” which is uninspiring at best and demoralizing and degrading for students at worst.

Another FemTechNet comrade and someone who teaches the hell out of Gender Studies, University of Washington Prof. Cricket Keating, has proposed that we make a Facebook group to share descriptive rubrics and strategies. We’re on Facebook as F-HELP (Fun and Hilarious Evaluative Language Practices). People can request to join in the conversation there. Cricket started the group and then the semester started and we all fell into our own courses and institutions, so let’s re-start now. Please don’t ask to join if you’re going to troll us, okay? You can also join the conversation by adding your comments below.

As we enter into a new September semester, I wish you all outrageous learning successes in weekly writing and grading.

PS. August 2020 Update – “Moving Online”

It seems unanimous that regular, low stakes writing assignments/active participation is a good way to help students keep on top of their work during the semester and not fall stressfully behind, which is especially easy to do in asynchronous/pre-recorded courses. And we’ve heard from students who finished the term online in the winter and took online courses in the Summer 2020, that some recognition by faculty on their weekly work helps them to feel seen and like there’s a point to it all.

With increased enrollment and other stressors and demands on our time this semester, I find even simpler rubrics serve an equal purpose. Here is one I came up with last year when my class size ballooned.

Thinking In/Thinking Out – Active Participation Notes

A descriptive grading rubric is a system of communication between teacher and student. I use this rubric for all assignments, and use it is the only grading I do for the Active Participation Notes until the end of the semester. The idea behind a descriptive rubric is that it is a quick way for me to communicate how you are doing in a weekly way. Ideally, this rubric will give you a way to assess how well you are demonstrating your engagement with the course. Over the course of the semester, what I’m interested in is your *trajectory* — where did you start and where did you end up?

Shines Bright like a Diamond (SB) – Question/comment is thoughtful and reflects that the student is engaged with the readings in a way that reflects some complexity.

Showing Up is Half the Battle (SU) – Question/comment shows that you showed up with a question/comment, but does not reflect an engagement with complexity of ideas/discussion, etc.

Hello…? (H) – Where are you? No show.

Please keep track of your weekly scores and at the end of the semester you’ll receive a cumulative grade out of 10. If you have shown sustained improvement over the term, your grade will reflect where you end up, not where you started!