The main goal of the Digital Citizenship Learning Playlist project was to co-design four digital citizenship playlists in collaboration with young people from youth-serving organizations in the Boston metropolitan area. Working together, we created four playlists, addressing specific questions that youth had about sharing personal information, credibility, careers, and digital rights and responsibilities. Where helpful, we sought to build upon learning resources that the Berkman Klein Center, through its Youth and Media (YaM) team, developed previously, and remix them to produce connected learning experiences and multimedia content for each playlist. We also wanted to include resources developed from our extended network of collaborators and, if necessary, create new ones.

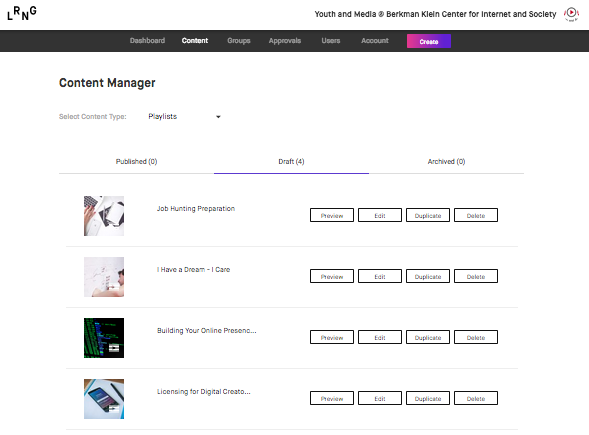

After 9 months, we have co-designed four playlists –each of them composed of six digital XPs and one badge. “Building Your Online Presence” addresses issues of privacy and surveillance; “Job Hunting Preparation” centers on job application and resume writing; “I Have a Dream–I Care” is about creating an advocacy campaign; and “Licensing for Digital Creators” focuses on creative rights and responsibilities. While the first three of these playlists build upon existing resources, the “Licensing” playlist includes a number of original resources that we developed in collaboration with the Cyberlaw Clinic at Harvard Law School. These new resources, such as “Parody”, “Public Domain”, and “Creative Commons Licenses” guides, and a general “Glossary of terms,” are now available on the Digital Citizenship+ Resource Platform.

We have also uploaded the playlists, XPs, and badges to the LRNG platform, and have been testing them using the demo site with our co-designers and other youth who have joined us during this final phase. Based on the feedback we have received thus far, we have continued to iterate on both the playlist sequencing and production-centered activities and have worked on the assessment criteria. However, given some of the timing and scheduling challenges we have confronted during this last phase, the playtesting has not been as comprehensive as we would have liked. As a result, we plan to continue playtesting and iterating during the summer so we can refine all the XPs and playlists and release them to the public on LRNG.

Co-design Challenges and Opportunities

The process of co-design was essential for our work. It allowed us to incorporate youth perspectives into the playlists and to ensure that the learning activities and multimedia resources were relevant for youth. We facilitated a series of workshops at four youth-serving organizations in the Boston metropolitan area, and, working together with groups of 8-12 youths, we went through all the phases of design thinking (e.g. empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test, iterate). At the workshops, we co-created a collaborative space in which we invited youth perspectives, participation, curiosity, and creativity. Using several tools such as persona maps, interview handouts, agile paper prototyping, and hybrid (digital/paper) playtesting, we were able to complete the co-design of the the four playlists, which, all together, consisted of 24 XPs and four badges.

By co-designing with youth from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, ethnicities, and educational levels, we were able to better understand how different youth interests and digital literacy skills interface with aspects of digital citizenship such as privacy, rights, responsibilities, and self-expression. The diversity of needs and interests among our co-designers allowed us to define learning outcomes that we did not consider in our initial plan. For instance, based on one co-design group’s unique interests, the playlist “Job Hunting Preparation” allows young people to develop resume writing and networking skills in preparation for their first job applications.

While both essential and rewarding, the co-design process also came with challenges. It demanded great flexibility and adaptability on our part. We adjusted our initial plans according to the schedules of the youth co-designers and the four youth-serving organizations that supported us. Although this created delays at the moment of executing our original plan, the time constraints made us think creatively about how to facilitate design thinking activities in an agile way, as well as how to collaborate remotely with the youth co-designers. We learned that testing and iterating final digital playlists drafts requires a considerable amount of time and energy from all the participants of the co-design process.

Overall, co-designing playlists around digital citizenship issues became an empowering experience for youth. They had the opportunity to share their own knowledge about this topic, consider the digital skills they would like to hone, and experiment with designing their own learning activities. This experimentation is important since youth do not usually participate in the design of learning and educational materials.

We recommend co-design as a participatory methodology for the creation of connected learning experiences and playlists. Based on our own process, we would like to offer five tips for co-designing playlists and learning experiences with youth.

-

Follow the five design thinking stages (e.g. empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test). Design thinking is an appropriate methodology because it allows one to place the learner at the center, integrate their needs, understand their interests and passions, and engage in hands-on prototyping and testing.

-

Invest in logistics and planning. Remember, time spent with co-designers is at a premium. Set aside time for several workshops. At a minimum, we recommend engaging in at least one workshop per design thinking stage, and at least two workshops for testing and iterating the complete playlist.

- Allot adequate time for playtesting and iteration. Co-design is an iterative process that requires testing and refining the final products. Testing a fully functional playlist requires a considerable amount of both time and help from motivated co-designers. If possible, collaborate with teachers or facilitators at the youth-serving organizations who can set aside time for engaging with a completed playlist as part of a class activity or a workshop.

- Establish a common language among the co-designers, and use this type of discourse in both the workshops and the content created. That is, make sure that both the adult facilitators and the youth co-designers understand what each other means with the language that they use. This goes both ways. The adults should follow up with the youth co-designers to make sure that any adult introduced language, particularly technical terminology, can be understood by the youth co-designers. In addition, the adults should be sure to clarify any unfamiliar terms that the youth co-designers introduce. Try to keep a balance between expert terminology and youth language when addressing complex themes.

- Be flexible. Co-designing can be a messy process where delays and unexpected situations can emerge given its participatory and collaborative dynamics. When facing unexpected developments, be ready to adapt to the needs of youth co-designers, and creatively try to turn constraints into design opportunities.

The LRNG Platform as a Playlist Technology

The LRNG platform is engaging, visually appealing, and easy to explore. The YaM team has an organization account that we have used to draft the co-designed playlists, XPs, and badges. The platform provides the tools for laying out the content in an engaging way that is visual, has little text, and lets the users explore interactive resources and submit creative content. The format works both in desktop and mobile formats, making learning possible virtually anywhere, at anytime.

The YaM team was responsible for uploading all content to the LRNG platform. Youth co-designers were able to explore the platform before the workshops in order to become familiar with the look and feel of the playlists, XPs, and badges. The young co-designers were able to engage with the platform more actively and thoroughly during the testing of the completed playlists.

For this final phase of the project, however, we used the demo version of LRNG. The demo version allowed us to publish our latest iterations of the playlists in a temporary manner so that we were able to update playlists according to the feedback we received, such as the co-designers learning activity submissions. Although the demo platform generally worked well, we experienced a server outage during one of the playtesting weeks that removed all submissions from a group of co-designers. The outage also created a problem for the teacher who was helping us with the playtesting. He had already designated time in his classroom specifically for playlist work, and this plan was compromised because the students were not able to log in during this interval.

Despite this technical challenge, as the YaM team worked on the LRNG platform over the course of this project, we found it very user-friendly. Five members of the YaM team uploaded and assembled the playlists, and two reviewed the submissions we received during playtesting. Assembling the playlists may have been improved by having more tools for browsing and sorting the XPs that the organization had already uploaded to the platform. Additionally, it may have been useful to have visual aids that signal if XPs are already being used in a particular playlist.

Although, as noted previously, the technology, overall, seemed to work well, we think that the LRNG platform might benefit from the creation of social spaces where youth can talk to each other, and to adults from the organizations that publish playlists. It may also be helpful to create a tool on the platform that allows learners to explore potential occupational opportunities, and network with employers.

Another area of potential platform improvement is in the types of submissions allowed by the platform. Initially, we co-designed resources with young people that required multiple types of submissions. For instance, an XP might ask a young person to create a visual submission and then provide a written description of what they hoped to achieve. Unfortunately, we were not able to find a way to incorporate both a text and an image upload. Greater interoperability between submission formats could provide new submission possibilities and innovative ways of teaching content.

Release and Scaling up

We plan to publish the four digital citizenship playlists on the LRNG platform this summer after additional testing and iteration. Our current playlists can still be improved, particularly with respect to the artifacts that the learners need to submit when they complete an XP. For instance, the feedback and submissions we have received thus far have demonstrated that we need to iterate on the instructions we provide for completing these production-centered activities.

Our release strategy includes the use of social media channels, websites, and newsletters to highlight project findings and to generate interest among educators and youth. We plan to use different media formats for promoting the release of the four digital citizenship playlists, such as a post on Medium, visual memes and GIFs on Twitter and Facebook, a dedicated page on the YaM website, texts blurbs on email lists, and a project summary in newsletters–both our team’s own and the “Berkman Buzz”. In particular, on social media, we would like to promote the playlists individually, highlighting each of them in terms of themes, skills, and narratives, and incorporate specific hashtags for each playlist. We also plan to publish the XPs and playlists we co-designed on our Digital Literacy Resource Platform, adjusting their format to the affordances of our website, and release them under the most recent version of the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0).

As part of our release plan, we would also like to organize a public event at the Berkman Klein Center where we can present the playlists to members of local youth-serving organizations. For this event, we would like to invite some of the most motivated youth co-designers who collaborated with us and encourage them to share their own experiences with the playlist co-design process.

Apart from reaching out to youth through social media channels, we aim to connect with teachers, practitioners, and other educators. This adult audience will play a crucial role in disseminating information about the playlists and using them as part of their curricular and extracurricular programs. As we have observed during our the testing phase, young learners are motivated to complete the playlists when they are presented as part of a class or a workshop. We want to connect with educators around the country who are interested in incorporating the playlists in their classroom activities. We would like to support them with guides and rubrics that help them understand how the playlists work, how to most effectively implement these learning exercises in their classroom, and how to support youth as they complete them. Finally, at a fundamental level, we hope that the publication of the four digital citizenship playlists on LRNG will be a form of outreach and marketing in itself. We hope that the success of both our own and our counterpart playlists will help bring new users to the platform and boost the audience for all the resources on LRNG.

We are aware that playlists, XPs, badges, and the LRNG platform offer opportunities for scaling up connected learning, by, for instance, providing access to meaningful production-centered activities to hundreds of youths and validating interest-driven learning with credentials. However, scaling up connected learning comes with a set of challenges, especially in terms of assessment, diversity, and sustaining the engagement of youths. For instance, as an organization, the YaM team does not have the capacity to assess the submissions of all the young users across the country who complete XPs and playlists.

As we have experienced during our co-design process, youth’s interests and passions are diverse and vary according to their socioeconomic and cultural contexts. Our playlists have been co-designed according to the needs and interests of specific audiences and contexts. Although we believe many youth can engage with these learning exercises, some activities may not have the same meaning and may not resonate in the same way as they did with our co-designers. Given that what is “meaningful” to a learner depends on their background, we then must consider: how can our playlists adapt to the diversity of youth contexts and backgrounds?

Advancing the field of connected learning

In order to advance the emerging field of connected learning playlist design, researchers, practitioners, educators, and technologists must work together to share playlist findings, test tools, and create spaces for co-designing with diverse groups of youth. Below are three key questions we believe the field needs to address in order to continue evolving.

- How do we create learning activities that match youth’s interests, are production-centered, and have “new” and “updated” multimedia resources, and, at the same time, are based on rigorous research and promote traditional literacy skills, such as reading and writing?

- How can playlist technologies such as the LRNG platform cultivate social support during the learning process and build social capital through, for instance, informal mentorship and increased collaboration among learners?

- When designing learning playlists for and with diverse groups of youth, what should we consider in terms of access to both co-design opportunities as well as the resulting resources? How can we make learning resources interoperable in the networked communication ecosystem and more accessible across contexts? How can we scale connected learning, taking into account the disparities in access to technology, social support, and digital literacy skills?